WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH Q&A

A Conversation with Rachel F. Seidman, Curator at the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum

As we celebrate Women’s History Month, Women Moving Millions had the privilege of speaking with Rachel F. Seidman, curator at the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum. Rachel is leading the museum’s latest initiative, We Do Declare: Women’s Voices on Independence, which marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence by examining how generations of women have experienced and defined the concept of independence—particularly through the lens of economic power. This multi-faceted oral history project, focused on the past 50 years, explores when, how, and why women have sought financial autonomy, and the lasting impact of their struggles and triumphs. While additional research is forthcoming, Rachel shares some early findings from her interviews, offering a glimpse into the resilience, ingenuity, and determination of women shaping their own destinies.

Women Moving Millions (WMM): Your new initiative explores when, how, and why women have sought independence in their own lives, through the lens of economic power. Since it’s Women’s History Month, can you share some of their most powerful stories?

Rachel Seidman (RS): One of my favorite stories I’ve collected so far is that of Emily Card, who played a critical but mostly forgotten role in getting the Equal Credit Opportunity Act passed in 1974. As some may know, before that turning-point legislation, most women could not get a credit card in their own name. By 1973, when Emily Card arrived in D.C. to be a legislative fellow in the office of Senator Brock, Republican of Tennessee, women’s groups had been agitating for several years on the issue of credit, and Congresswoman Bella Abzug had introduced legislation. But Abzug wasn’t on the banking committee and didn’t have the clout to get it passed. Senator Brock was on the banking committee but wasn’t convinced the topic merited his attention. Having faced discrimination at banks herself, Card immediately set to work, compiling the research that the National Organization for Women and other groups had undertaken, and making sure that Brock saw thousands of letters from women around the country explaining how angry they were about what they faced. Finally, Brock agreed to take on the issue, and tasked Card with writing the legislation, which she did. She then called every woman she could find on the Hill, in either party, to lobby their bosses to support the bill, which passed unanimously. She still remembers how, even though there was a dress code that forbade women from wearing trousers in the Senate, she wore her white pantsuit and platform shoes to watch the bill’s passage. To me Card’s narrative offers an amazing example of how change happens—showing

both how progress relies on the efforts of many over time, but also the remarkable impact a single, determined woman can have.

WMM: How has the notion of women’s economic independence evolved throughout history?

RS: By no means the whole answer—that would take more time and inches on the page than we have—but one of the key historical facts that’s really important to understand is the old British common law concept of coverture, which came over to America in the colonial period. Under coverture, when a man and a woman married, the woman legally disappeared. A married woman was “covered” by the man’s legal entity; as a result, she could no longer sign contracts, own property, or control her own wages. Due to women’s political organizing, over time, married women’s property acts and other legal challenges chipped away at coverture. But that long history undergirds attitudes that lasted well into the twentieth century, and was definitely part of why we needed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. Emily Card told us that in the 60s and 70s, when a woman got married, credit bureaus literally took her physical file and placed it inside the husband’s file—what a remarkable metaphor for the ongoing power of the notion of coverture!

Another thing I’ll say is that it’s really important to understand that women’s experiences have not all been the same, whether throughout history or today. In 1810, in Washington, D.C., Alethia Tanner, an enslaved woman, purchased her own freedom with money she had earned by selling vegetables on public grounds on the north side of the White House, known today as Lafayette Park. Hers is a powerful reminder that the whole concept of “independence” in women’s lives has been deeply shaped by factors beyond just their sex. What more profound act of economic independence could there be than purchasing one’s own freedom; and what more egregious betrayal of the ideals in the Declaration of Independence could there be than the need for her to do so? One of the things we hope this oral history interviewing project will reveal is how women’s attitudes toward economic independence—and what that means to them—have been shaped by their own experiences in the world, but also by their family and community history and memory.

WMM: So many times women’s contributions to society are buried, overlooked, or not duly recognized. What are we missing when we don’t look back at the history of women’s achievements?

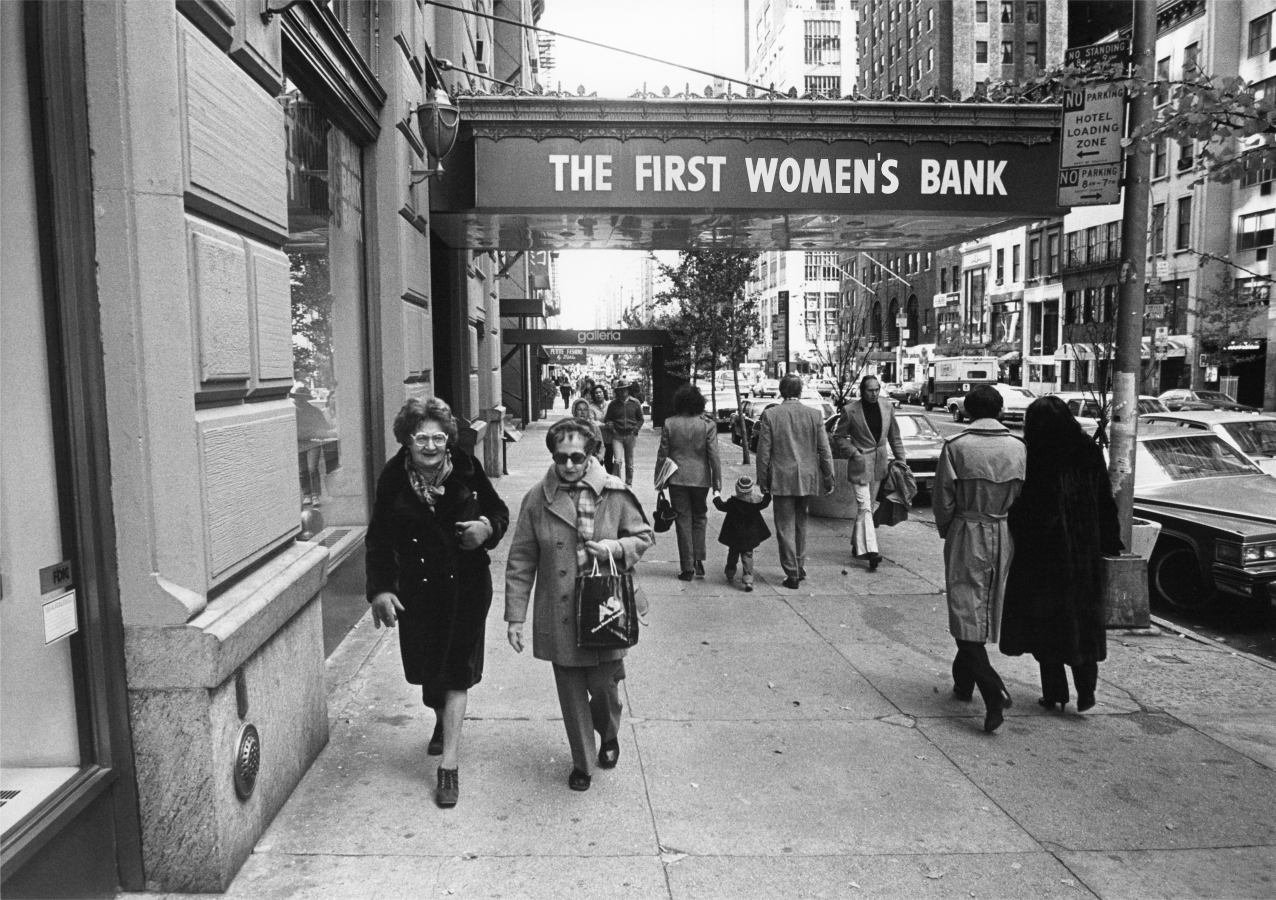

RS: So many amazing stories of ingenuity, tenaciousness, and chutzpah! One day a few years ago I was sitting in the office of Stephanie Lipscomb, the branch manager of my local bank. I noticed she had a photograph of herself with Cecily Tyson and President Barack Obama when he gave Tyson the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016. When I asked her why she had been there that day, she explained that she and Tyson had become friends in the 1980s, when Tyson started banking at Washington D.C.’s Women’s National Bank, later called Adams National Bank, (after Abigail Adams). I was stunned; after studying American women’s history for more than thirty years, I’d never heard of women’s banks. I told Stephanie then and there that I was going to come back and interview her one day. I was thrilled to be able to include her story in We Do Declare, and others who had participated in the women’s bank. They taught me so much about how, after the passage of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974, women realized that bias would not disappear automatically. Some set up women’s banks around the country to create institutions where women would feel comfortable, get financial education, and would be given a fair shake as customers, borrowers, and employees. Most petered out over time, but their legacy remains. Rosemary Reed, whom I interviewed, was passionate about the impact the Adams Bank had on her own ability to get support for her entrepreneurial endeavors after having faced sexism at mainstream banks. Women’s banks are a great example of women’s ingenuity and determination to create change by institution building. Some of these institutions we’ve heard about, but so many others have been forgotten or overlooked. What I love is that we are surrounded by clues—like that photograph on a bank manager’s shelf—and if we pay attention and learn to ask good questions, we can recover and share powerful stories that help us understand and explore innovative strategies women have taken in the past to address inequities and create new opportunities.

—

About Rachel F. Seidman: Rachel F. Seidman, PhD, is curator at the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum, where she is directing the oral history and education project We Do Declare: Women’s Voices on Independence. In her role, Seidman will work closely with the director and the museum’s future curators, educators, and public engagement teams to identify, shape and develop the museum’s historical research agenda, and share those insights with the broader public through online and in-person channels, programs, and exhibitions. As a member of the curatorial team, Seidman will help to build a collection, develop overarching interpretive framework, and design and deliver the museum’s public history initiatives. Previously, Seidman was an award-winning curator at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum. Before coming to Washington, D.C., Seidman directed the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. A published historian, Seidman has also taught at Duke University and Carleton College and was a 2019 Fulbright Scholar at the University of Turku in Finland. She holds a PhD in history from Yale University, and a BA from Oberlin College.

About Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum: We are the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum. We passionately believe that we all benefit from a deeper historical understanding of our nation. Our museum expands the story of America through the often-untold accounts and accomplishments of women—individually and collectively—to better understand our past and inspire our future. Our mission is to create space for women’s history on the National Mall in Washington, DC, deepen our nation’s stories, and inspire conversation, connection, and change. Our ultimate vision is a more representative history, a more collective future. Women’s history is American history.

About Women Moving Millions: Women Moving Millions is a dynamic, impact-led community on a mission to catalyze resources to power the movement for gender equality. Our 400-strong membership has collectively committed over $1B to improve the lives of women and girls. Through collaborative leadership (resources, social capital, and expertise), we seek to drive greater impact and accelerate progress. By transforming how we give and invest, we remove barriers for leaders and innovators, inspiring bolder investments from a diverse ecosystem of funding partners. Together, we are building a world where all women have full autonomy, freedom, and agency over every aspect of their lives.

Photo: Courtesy of Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum: Street Scene New York [outside First Women’s Bank], 1975. Photo by Calle Hesslefors/ullstein bild via Getty Images.